The death in January of The Fall's Mark E Smith, and the subsequent internet deluge of tributes and reflection pieces has rekindled my interest in this most unusual

and perplexing band. As well as re-visiting the music, I have read three relatively recent books about The Fall, two by former members and one by an obsessive fan.

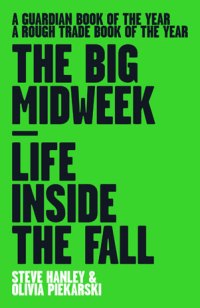

Steve Hanley and

Brix Smith Start’s autobiographies couldn’t be more different. At times in The Big Midweek, Hanley, The Fall’s

bassist from 1978 to 1998, might be writing about working on a building-site

rather than touring the world with a highly combustible art rock band. He is so

low-key and self-effacing, it’s no surprise to read that he enjoys his current

job as a school caretaker. It’s also easy to see how important he was to the

band as a calm and solid presence willing to tolerate the often provocative and

domineering Smith. The latter needed

good, but passive players to realise his vision and Hanley and guitarist Craig

Scanlon fitted the bill. Co-written by Olivia Piekarski, this is a

matter-of-fact account of twenty years in The Fall that contains several good-natured

anecdotes about Scanlon and Marc Riley (Hanley’s childhood friend).

As befits someone

whose childhood was shaped by regular trips to Disneyland and visits to

Hollywood sets, Brix Smith Start’s memoir The

Rise, The Fall and The Rise is a lively, technicolor affair in which the

erstwhile Fall guitarist charts her journey from broken homes to college band

to the fateful concert in Chicago where she met Mark E Smith, her future

husband and band-mate, to her later career as the co-owner of a fashion boutique.

Smith Start has a sharp eye for details

relating to clothes and locations and for Fall fans, her description of Mark’s

flat in Prestwich in 1982 will be worth the price of the book alone. Smith

presented such a formidable public image over the years – alternatively

derisive and defensive on record and in interviews – that it’s fascinating to

read about ordinary details such as his home life, his working habits and the

cruise he went on with Brix’s family.

Dave Simpson’s The Fallen is primarily about Smith as

seen through the eyes of some of the sixty-plus people who have been in The

Fall. In interviews, Smith often described himself as ‘bloody-minded’ and that

is borne out by the testimony of the various ex-members whose memories create a

picture of an artist who controlled whoever was in the band like a cantankerous

sergeant-major and who exerted his control even to the commercial detriment of

The Fall. Hanley and Smith Start both refer to Smith’s tendency to

self-sabotage, regularly following up albums that had commercial appeal with harsher

sounding, slap-dash, efforts.

Of the three books,

this is the funniest and the one that would be of most interest to the non-fan.

Such is the wealth of recorded material and accompanying stories, a mini industry

of books about The Fall might yet emerge.